As China’s Belt and Road Initiative enters a new era, CIPE examines Beijing’s plans to go smaller, greener, and smarter. The new focus on what Beijing called “integrity-based cooperation” is a tacit acknowledgment of the corruption that plagued the BRI’s first decade. China’s commitment to fund livelihood assistance programs could bring aid directly to the people who need it, and increased reliance on private sector capital suggests a lower tolerance for high-risk loans that can turn out badly for both China and its borrowers.

This brief compares the BRI’s original objectives with China’s new stated priorities and actions. It advises countries to remain clear-eyed about the risks and urges observers to pay close attention to whether the promise of “integrity-based cooperation” bears out.

- Has an evolution really taken place?

- What does a “small and beautiful” BRI look like?

- What are the implications for recipients of BRI funding?

Read on for CIPE’s full analysis.

A Smaller, Greener, Smarter BRI

China recently convened the World Internet Conference Digital Silk Road Development Forum, where participants from nearly 50 countries discussed opportunities for economic cooperation, from data sharing to e-commerce facilitation. The conference came six months after Chinese President Xi Jinping’s keynote address to the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, where he reaffirmed his vision of a smaller, greener, and “smarter” BRI that has come to be described as “small and beautiful.”

The initiative’s core objective is unchanged: boosting China’s economy by opening foreign markets to Chinese exports and securing the country’s supply chains.

Xi’s speech raised many questions about the future of the BRI. Among them: Has an evolution truly taken place? What does a “small and beautiful” BRI really look like? What are the implications for recipients of BRI funding? Xi’s remarks at the Third BRI Forum reveal that the initiative’s rebranding is a tactical move to improve China’s image and signal a shift from the “old” construction industries toward a focus on China’s new economic priorities in the clean and advanced technology sectors. The initiative’s core objective is unchanged: boosting China’s economy by opening foreign markets to Chinese exports and securing the country’s supply chains. Consequently, there remains a significant risk that below market pricing on Chinese goods and services in heavily subsidized BRI industries could wipe out local industries and prevent the emergence of non-Chinese competitors around the globe.

The BRI’s Foundation as an Economic Tool

Since its earliest conception as the “Silk Road Economic Belt” the BRI has had China’s integration into the global economy at its foundation. In his 2013 speech unveiling the BRI, Xi laid out five objectives. It is notable that four of the five objectives are explicitly economic in nature. Each one plays a significant role in bolstering China’s growth strategy, which emphasizes government support for strategically chosen industries, complete control over supply chains, and reliance on exports to compensate for insufficient domestic demand.

Each objective bolsters China’s growth strategy, which emphasizes government support for chosen industries, complete control over supply chains, and reliance on exports to compensate for insufficient domestic demand.

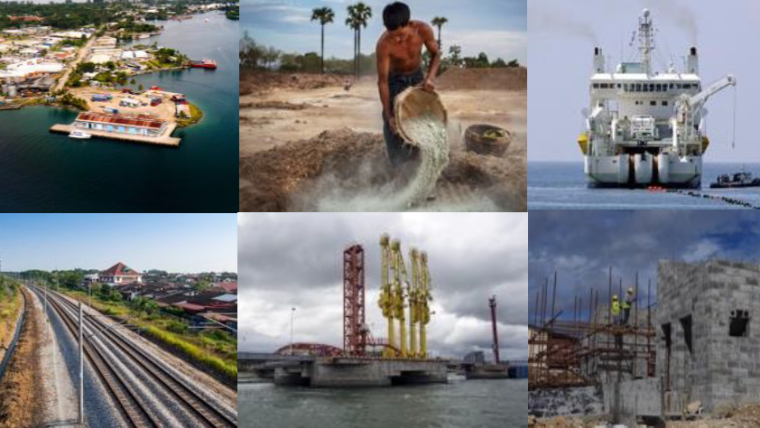

The first objective is increasing economic policy communication, which has manifested as the establishment of new multilateral mechanisms and other moves to influence and align policies and governance models of BRI countries with Chinese preferences. The second objective, improving road connectivity, has been the most visible aspect of the BRI: large infrastructure projects like roads, ports, and dams are hard to miss and tend to be expensive. These projects contribute to China’s economic agenda by facilitating the transport of manufacturing inputs to China and the expansion of trade routes out of the country, thereby contributing to the third objective—eliminating trade barriers—in tandem with China’s push to lower tariffs.

The fourth objective, enhancing local currency convertibility, serves the dual purpose of reducing the transaction costs of trade for China and internationalizing the renminbi. Expanding the renminbi’s use would increase Beijing’s influence over the international financial system and reduce the effectiveness of economic sanctions against Chinese entities. Although it has gained some traction, most analysts agree that the renminbi’s potential for widespread use is limited without major changes to China’s economic policies.

Finally, the fifth objective of fostering people-to-people connections is aimed at enhancing China’s global influence through political, cultural, academic, and media exchanges. For example, Beijing exports its authoritarian governance model through party-to-party relationships and seeks to shape global academic and media narratives about China through initiatives like the Belt and Road Think Tank Cooperation Alliance and the Media Cooperation Forum on Belt and Road. It also funds and facilitates trips to China for foreign government officials and draws growing numbers of foreign students to deepen their understanding and sympathy for Beijing’s worldview.

What Does “Small and Beautiful” Really Mean?

Xi Jinping enumerated eight priorities for the BRI’s second decade during his October 2023 speech at the Third BRI Forum that operationalize the “small and beautiful” theme that permeates Chinese descriptions of the BRI. The priorities point to a future in which projects are smaller, greener, and smarter.

China’s logical next step is to maintain the growth through state-driven capture of global market share—leading to a BRI that is smaller, greener, and smarter but no less consequential for the world.

A ‘smaller’ BRI is one that finances fewer infrastructure megaprojects in favor of projects that are relatively cheaper and more limited in scale. Analyzing data from nearly 21,000 BRI projects in AidData’s Global Chinese Development Finance Dataset shows that China’s annual BRI financing commitments, measured in constant 2021 U.S. dollars, peaked in 2015 and has declined almost every year since then. It also shows that the average size of new financing commitments since 2018 onward has been less than half the average size of commitments in 2015. Focusing on smaller projects eases reliance on large state-backed loans, carries less risk for financial backers, and can offer quicker results. Some of this change may be driven by Xi’s promise at the Third BRI Forum to fund and carry out 1,000 small scale livelihood assistance programs.

A ‘greener’ BRI has focused on growing clean energy projects and cutting back on dirty ones. China has rapidly expanded production and export of green products including battery electric vehicles (BEV), lithium batteries, and solar panels, and many of these products are beginning to factor into new BRI projects. A greener BRI benefits China in multiple ways, including by locking in the country’s dominance in clean technology, blunting criticisms of China as the world’s top carbon emitter, and appearing to demonstrate responsiveness to growing calls for rich countries to step up climate support for more vulnerable states.

The ‘smarter’ BRI follows a similar playbook but in digital technologies including ICT infrastructure and smart cities. By intensifying its focus on the technologies that underpin modern trade—according to at least one estimate, China’s cross-border e-commerce trade in 2023 grew by over 15 percent year-on-year—China seeks to further embed itself at the center of global supply chains and expand opportunities for the renminbi’s use in international trade.

A New Approach to Old Objectives

As the BRI shifts to a smaller, greener, and smarter model, there is cause to hope that positive change could occur. The new focus on what Xi called “integrity-based cooperation” is a tacit acknowledgment of the corruption that plagued the BRI’s first decade. China’s commitment to fund livelihood assistance programs could bring aid directly to the people who need it, and increased reliance on private sector capital suggests a lower tolerance for high-risk loans that can turn out badly for both China and its borrowers.

Continuity in the BRI’s objectives means that countries must remain clear-eyed about the risks.

Even so, continuity in the BRI’s objectives means that countries must remain clear-eyed about the risks. Throughout the first decade of the BRI, China exported construction materials and labor to foreign countries at below market costs and kept bloated domestic industries afloat after years of state-driven investment led to production overcapacity. One consequence on these non-competitive behaviors was China’s absorption of global market share in BRI industries. China’s move away from infrastructure megaprojects coincides with a shift in Beijing’s domestic economic focus toward advanced and green technologies such as lithium batteries, solar panels, EVs, and telecommunication systems. Many of these industries are heavily subsidized and appear to follow much the same trajectory of state-driven growth as China’s construction-related industries in previous decades.

From 2016 to 2022, for example, Chinese state subsidies for electric and hybrid vehicles amounted to $57 billion. China has also devoted significant resources to becoming a global leader in telecommunication technology and achieving a more than 80 percent share in the global market for solar technology manufacturing.

As evidenced, systematic and substantial government support has significantly expanded production capacity in these industries, far surpassing domestic demand. China’s logical next step is to maintain the growth of these industries through state-driven capture of global market share—leading to a BRI that is smaller, greener, and smarter but no less consequential for the world. Unless actions are taken to level the playing field, the BRI’s second decade will likely repeat the first decade in a new set of industries. This could lead to global crowding out effects, where national champions nurtured by China overshadow potential and emerging competitive and innovative players in these industries.