China has undercut market mechanisms and given itself an unfair advantage in critical mineral production. It has dominated the critical minerals market by subsidizing its firms and failing to abide by international standards. The results include competition forced out of the market, consumers left with fewer choices, ecosystems and livelihoods destroyed, and supply chains made less secure. Reversing this damage and reviving a healthy market that delivers for producers and consumers alike will require a whole-of-society effort in which governments, civil society, and the private sector work together to implement solutions that work for all.

In this policy brief we explore:

- How China dominates the supply chain in the DRC and Indonesia. DRC produces 70% of the global supply of cobalt, and Indonesia 55% of the world’s nickel.

- China’s use of non-market practices.

- The consequences of low standards.

- Best practices to mitigate China’s corrosive investment practices.

Examining Chinese Practices in the Global Critical Minerals Market

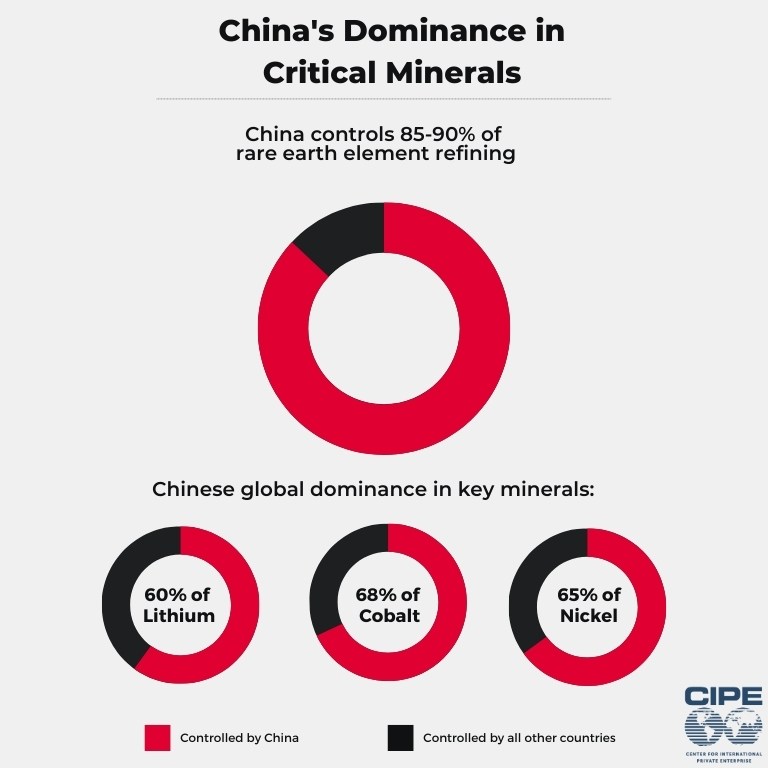

Governments and private sector actors are clamoring to design and manufacture more cost-efficient, low-carbon technologies. Lithium, cobalt, nickel and other critical minerals—a U.S. government designation for non-fuel components of energy technology that are at high risk of supply chain disruption—play a key role in that transition. Dominating these minerals’ production is a key element of China’s strategy to secure a pathway to high-income status. Consequently, Chinese enterprises have invested heavily in critical mineral mining and processing, with government support. In 2023, China accounted for 85% to 90% of global rare earth element mine-to-metal refining. Chinese smelters refined 68% of the world’s cobalt, 65% of its nickel, and 60% of lithium suitable for use in electric vehicle batteries. This brief explores the implications of China’s role in mineral extraction by highlighting Beijing’s dominance in Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, two major mineral-producing countries. It assesses the damage to governance and markets and offers steps that governments, the private sector, and civil society can take to repair a core sector of the global economy.

Critical Links in Critical Sectors: The DRC and Indonesia

Since the early 2010s, China has poured substantial amounts of capital into mineral extraction and processing in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Indonesia. In the DRC, which produces over 70% of the global cobalt supply, Chinese mining companies account for three quarters of cobalt output. The companies range from state-owned enterprises to private and mixed ownership structures. However, differences in governance and motivation between company types are murky because private enterprises are typically required to incorporate Chinese Communist Party representatives into their decision-making structures. CMOC Group Limited, a partly state-owned Chinese company that changed its name from China Molybdenum Company Limited in June 2022, became the largest private sector player in the DRC after it purchased the majority stake in the Tenke Fungurume Mine (TFM) in 2016 from Freeport-McMoRan Inc. TFM is one of the DRC’s largest copper and cobalt extractors, producing 12% of global cobalt output.

In Indonesia, which produces more than 55% of the world’s nickel, Chinese firms back more than 90% of nickel smelters. The Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP) exemplifies China’s increasing stake in critical mineral extraction and refining. IMIP was developed in partnership between domestic Indonesian firms and the Tsingshan Group, a private Chinese enterprise that became Indonesia’s largest nickel investor in 2014. IMIP has become Indonesia’s largest nickel processing site, employing 43,000 workers in 2020.

Flooding the Market with Cheap Minerals: China’s Non-Market Practices

Although Chinese investment has supported the expansion of mining industries and created employment around the world, Chinese firms’ use of non-market and anti-competitive practices has created an uneven playing field that forces competitors out of the market. A supply glut of cobalt, lithium, and nickel driven by massive overproduction has plummeted prices to levels that are unsustainable for many companies. Unlike their counterparts from other countries, Chinese firms can weather the drop in prices thanks to Beijing’s financial support and a willingness to disregard international standards. While technological innovation has contributed to Chinese firms’ success, they also skirt environmental standards, use forced and child labor, and erect barriers to entry. These cost-reducing practices allow them to keep prices artificially low.

Non-market practices enable Chinese firms to sell their products at prices that responsible businesses from other countries cannot compete with.

For example, the U.S. recently sanctioned a subsidiary of Zijin Mining Group, a fast-growing player in the DRC and elsewhere, for collaborating with the government of the Chinese province of Xinjiang to use forced labor. In addition, cobalt traders in the DRC, many of whom are Chinese, Indian, or Lebanese citizens, supply minerals extracted by thousands of child miners to Chinese mining and refining companies. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, Chinese smelters cut costs using technologies harmful to the environment. They also collaborate with Indonesian miners who destroy protected areas using counterfeit permits. These practices enable Chinese firms to sell their products at prices that responsible businesses from other countries cannot compete with.

The Governance and Economic Consequences of Low Standards

Competitors are not the only victims of Chinese firms’ practices: there are consequences for governments and purchasers of refined metals, too. Driving down the price of metals reduces the revenues of host governments, which maintain a stake in many mineral ventures. In some cases, Chinese firms have cheated outright on their agreements. CMOC’s license to operate TFM was suspended in 2022 after it was found to have fabricated reserve levels to dodge royalty payments. The ensuing legal dispute halted mining operations for nearly a year until CMOC agreed to pay an $800 million settlement and $1.2 billion in dividends to address profit-sharing imbalances.

For purchasers of refined ores, including manufacturers of automobiles, semiconductors, and electronics, China’s broad control of mineral refining poses both security and economic risks.

Chinese firms have also established a monopsony over mineral processing in the DRC and Indonesia, giving them significant influence over the price of raw metals. As a result, the miners themselves—of which as many as 30% are small-scale artisanal miners—receive a smaller share of mineral revenues. Meanwhile, Chinese firms establish relationships and exert influence over local officials who seek to pocket revenues from fabricated fees and taxes, undermining trust and complicating central governments’ efforts to take on corruption. Over the long term, this growing distrust and inequality risks exacerbating simmering tensions and could lead to increased levels of crime and violence. This is especially a concern in regions with active anti-government insurgencies like the DRC’s Katanga region, where TFM is located, and Indonesia’s Central Sulawesi province, where IMIP was built.

For purchasers of refined ores, including manufacturers of automobiles, semiconductors, and electronics, China’s broad control of mineral refining poses both security and economic risks. With Chinese firms suppressing prices, companies have few alternatives to Chinese suppliers, making supply chain diversification more costly and difficult. Chinese firms’ low standards also increase reputational and regulatory risks for companies whose consumers demand responsibly sourced products.

Toward a Fairer and More Competitive Mineral Market

Chinese firms’ low standards and persistent oversupply, buoyed by non-market practices, pose a long-term challenge for governments, the private sector, and civil society alike. Some China-linked entities have made moves to raise the standards of Chinese firms, such as the China Chamber of Commerce of Metals, Minerals and Chemicals Importers & Exporters, which published its Due Diligence Guidelines for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains. However, participation is often voluntary and subject to weak oversight. Thus, it is incumbent upon stakeholders across all sectors to apply pressure on China to raise its standards and create a level playing field.

Civil society and private sector actors have a key role to play in ensuring the mining and processing sector is competitive, secure, and ethical.

In the DRC, President Felix Tshisekedi’s government succeeded in renegotiating a minerals-for-infrastructure deal signed under its predecessor that will net the DRC an additional $4 billion in infrastructure funding on top of the original $3 billion that was promised but never delivered. The DRC government’s success shows that when governments insist on a fairer distribution of benefits, they can win. At the same time, governments need to establish policies that protect their gains and ensure resources are used wisely and transparently. For instance, creating independent government audit and assurance mechanisms to oversee implementation of mineral investment agreements can provide public accountability. Similarly, establishing disclosure frameworks that build on international standards such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) Standard, Global Reporting Initiative, and the OECD principles for responsible business conduct can reduce opportunities for illegal or unethical activity by ensuring regular public data disclosure, especially for ventures backed by foreign entities. Governments should also establish multi-stakeholder fora to discuss the impacts of foreign investments and review the terms and implementation of agreements with private sector and civil society groups.

Civil society and private sector actors have a key role to play in ensuring the mining and processing sector is competitive, secure, and ethical. To address the challenge of low-standard, low-cost China-linked minerals, some companies have proposed creating the option to sell sustainable, transparently produced minerals at a higher price on metal exchanges. However, this green premium proposal faces challenges including how to define qualifications for the premium, establish monitoring mechanisms, and expand still-nascent demand. Civil society organizations are well suited to support this and other private sector-led solutions through their expertise in convening stakeholders, providing oversight, and mobilizing public support for higher standards.

By subsidizing its firms and failing to abide by international standards, China has undercut market mechanisms and given itself an unfair advantage in critical mineral production. The results include other companies forced out of the market, consumers left with fewer choices, ecosystems and livelihoods destroyed, and supply chains made less secure. Reversing this damage and reviving a healthy market that delivers for producers and consumers alike will require a whole-of-society effort in which governments, civil society, and the private sector work together to implement solutions that work for all.